The Burden of Black Skin: How Racism is Taught to the Masses

Ta-Nehisi Coates writes to his son regarding the burden of black skin in his moving memoir, “Between the World and Me.” The memoir takes place in modern-day Baltimore—much different from Frederick Douglass’s Baltimore.

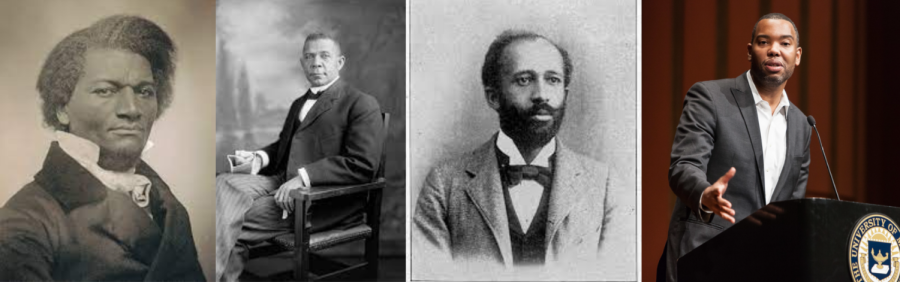

Walter Bowne/Canva/Wikipedia Commons

Black leaders and writers and activists have spanned the generations: Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, W.E.B BuBois, and Ta-Nehisi Paul Coates

When Frederick Douglass took his first steps into the home of his new owners—the Auld family—he first noticed the kind eyes of Mrs. Sophia Auld. “She was a woman of the kindest heart and finest feelings” (Douglass 40). Baltimore was kind to Frederick Douglass; the blue-collar city was beginning to recognize and oppose the abuse of slaves. Despite this growing ideal, Douglass was still a lucky man.

Under Mrs. Auld’s care, Frederick Douglass was always fed, rarely scolded, and never beaten. His new slave duties provided him with minimal discomfort. Mrs. Auld even supported Douglass’s wish to become literate, which, at the time, was very illegal. However, this “era of good feelings” didn’t last long.

Mr. Auld—a sour, tyrannical master—soon discovered his wife’s “humanity” towards their slave. He immediately stopped it by scolding her for not treating Douglass as an object. Soon, everything changed. To please her husband, Mrs. Auld worked Douglass to exhaustion. She berated him and flogged his body for even the slightest misstep.

How had a simple scolding changed the entire relationship between a mistress and her slave? Mr. Auld taught his wife a way of violence towards Douglass. Mrs. Auld would still be kind to Douglass if this were not the case. Evidently, it seems that racism is wholly institutional. Various historical examples support that—rather than being a natural phenomenon—racism is a manufactured ideology taught to the masses through word-of-mouth, social ignorance, and misinformation.

As a prominent black figure and author of his autobiography, “Up From Slavery,” Booker T. Washington carried his own history of racism. In “Up From Slavery,” Washington recounts personal testimony of institutionalized racism from his early life as a slave up to the creation of his life’s work: the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

However, during his struggle to create a school in one of the poorest areas of the country, Washington unexpectedly finds biracial support for his venture. While they understood that the Tuskegee school would primarily educate blacks, the white community embraced Washington’s idea. They knew that any attempt to educate the freedmen and women would benefit the town, and therefore, them.

In fact, “a canvass was made among the people of both races for direct gifts of money” (Washington 132) to help fund the school. Everyday strangers who could barely afford their own cost of living had recognized the Tuskegee Institute as a cause worth donating.

From Booker T. Washington’s perspective, it’s clear that ignorance of fundamental reality is a driving factor of racism. Whites and nonwhites, when placed in similar societal roles, begin to realize how similar they actually are. Conversely, wealth often detracts white people from the African American community, making them entirely ignorant of the latter’s struggles.

Even in the modern day, this societal divide among races rears its ugly head.

Literary icon Ta-Nehisi Coates writes to his son regarding the burden of black skin in his moving memoir, “Between the World and Me.” The memoir takes place in modern-day Baltimore—much different from Frederick Douglass’s Baltimore. Within its pages, Coates describes the horrors of the city and the overwhelming presence of “guns, fists, knives, crack, rape, and disease” (Coates 17).

He believes that not only are some whites taught to look upon the nonwhite community with distaste, but society teaches black youth to think that America isn’t meant for them. Yet, who could blame them; “but a society that protects some people through a safety net of schools, government-backed home loans, and ancestral wealth but can only protect you with the club of criminal justice has either failed at enforcing its good intentions or succeeded at something much darker” (Coates 18).

Coates lives with one foot in two separate worlds: the brutal streets of Baltimore and the utopian suburbs of prosperous, white America. Both worlds are light years apart. The reports of systemic inequality in modern-day America prove that racism is fabricated and taught through misinformation.

The congressional debate over critical race theory is a fresh example of Coates’s beliefs.

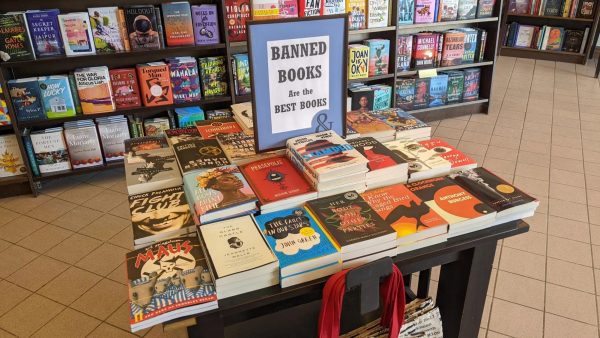

As the public looks further into the experiences of the African American community, they begin to realize the true identity of racism. This enlightenment has produced one of the first pieces of legislation in American history regarding the teaching of racist abuses. The bill would put the teachings of Douglass, Washington, and Coates in legal writing—allowing American students to learn how racism is taught in society. Ironically, however, the solution seems to be an example of the problem.

Critical race theory has seen significant pushback in the political theater. Some legislators believe that teaching students about the failures of American society would paint the country in a bad light. Others don’t see the benefits because they believe the institution is a natural phenomenon. While the former may be true, the latter is most certainly not. These legislators are influenced by prejudiced ideas passed down from their parents, which causes them to believe that racism is natural. Consequently, politicians incorrectly educate the public on the origins of racism, and the cycle of misinformation unfortunately continues.

As history shows, racism is a manmade ideology that is taught to the masses.

From what is seen in Frederick Douglass’ accounts, it spreads rampantly by word-of-mouth. It is also taught through pure ignorance; people that are socially separated from other races often seem to look upon others dispassionately. Even the oppressed are misinformed about racism. Ta-Nehisi Coates believes that black youth watch the beauty of American progress from afar. In a sense, they are taught that America isn’t meant for them. Coates’s beliefs about racism are also seen in politics. Legislators’ actions lead the public to believe that critical race theory isn’t substantial enough to be taught in schools.

These actions lead some to think that racism isn’t taught and passed down—in reality, it’s the complete opposite.