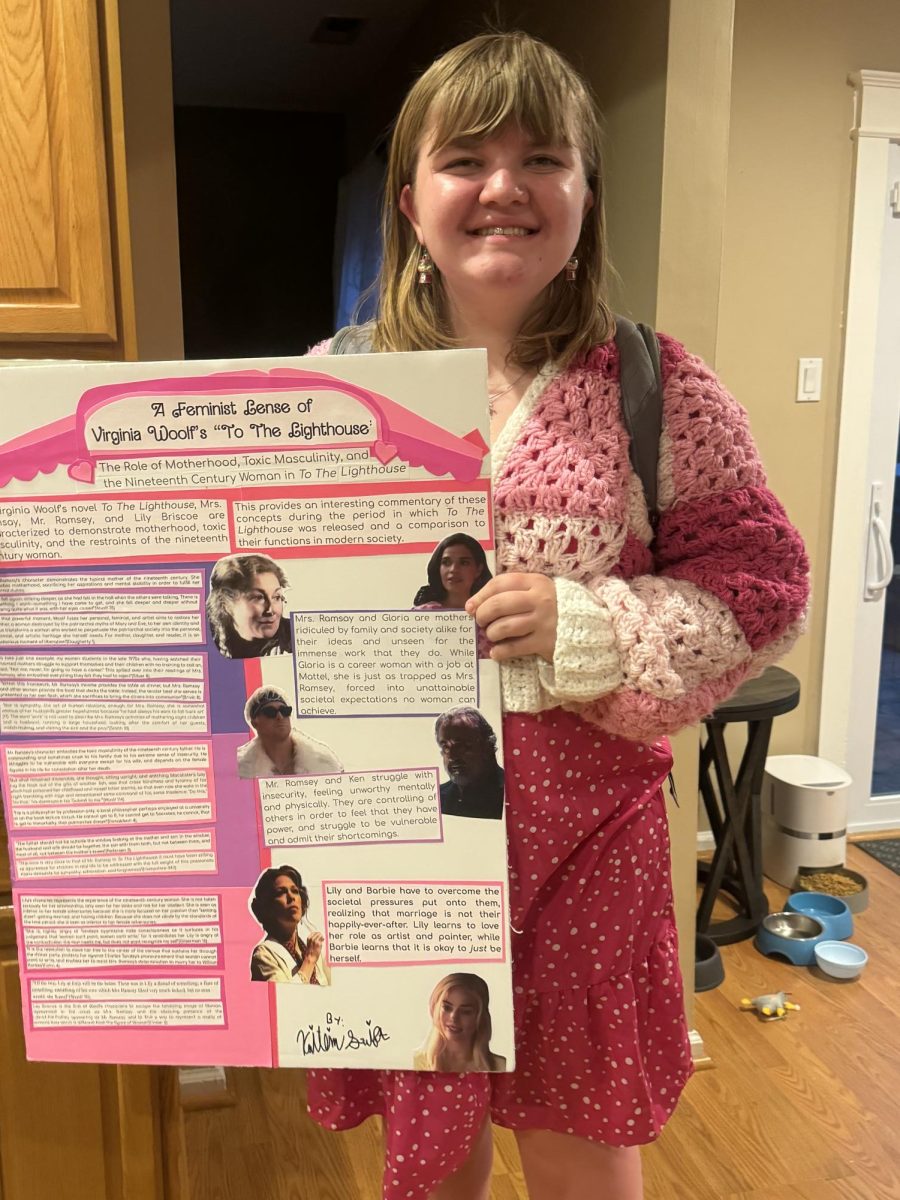

In Virginia Woolf’s novel To The Lighthouse, Mrs. Ramsay, Mr. Ramsey, and Lily Briscoe are characterized to demonstrate motherhood, toxic masculinity, and the restraints of the nineteenth century woman. This provides an interesting commentary of these concepts during the period in which To The Lighthouse was released and a comparison to their functions in modern society, as demonstrated by the Barbie movie.

Mrs. Ramsay’s character demonstrates the typical mother of the nineteenth century. She embodies motherhood, sacrificing her aspirations and mental stability in order to fulfill her maternal duties. She constantly consoles her husband and children, giving and giving them the love they desire until she has nothing left, “she felt again, sinking deeper, as she had felt in the hall when the others were talking, There is something I want—something I have come to get, and she fell deeper and deeper without knowing quite what it was, with her eyes closed” (Woolf 78). She has lost sight of her passions and dreams due to her devotion to Mr Ramsey and her children.

Mrs Ramsey’s character is inspired by Woolf’s mother, and her added perspective allows for a deeper analysis of the meaning of motherhood. “In that powerful moment, Woolf fuses her personal, feminist, and artist aims to restore her mother, a woman destroyed by the patriarchal myths of Mary and Eve, to her own identity and thus transforms a woman who worked to perpetuate the patriarchal society into the personal, feminist, and artistic heritage she herself needs. For mother, daughter, and reader, it is an audacious moment of liberation” (Daugherty 1). Mrs. Ramsey’s character is more established than the stereotypical maternal archetype of the time, and the audience gets to experience the first-hand thoughts and feelings of the nineteenth century mother.

This added analysis of motherhood provides an interesting contrast between its role in the nineteenth century and its role in the modern day. While Mrs. Ramsey’s character was the ideal in 1927, her character in modern day is one that women do not strive to imitate. “To take just one example: my women students in the late 1970s who, having watched their divorced mothers struggle to support themselves and their children with no training to call on, said, “Not me; never; I’m going to have a career.” This spilled over into their readings of Mrs. Ramsay, who embodied everything they felt they had to reject” (Silver 8). Mrs. Ramsay may have been the pinnacle of what a woman should be when To The Lighthouse was published, but the societal expectation of women in the nineteenth century as compared to women in the twenty-first century is drastically different.

Mrs. Ramsey takes on the burden of managing the affairs of the household, despite the fact that her husband Mr. Ramsey is the typical head of household. The stress of managing all of the practices and plans of the Ramsey family deteriorates Mrs. Ramsey, causing her immense anxiety as shown by her unspoken conversation with Lily. “I am drowning, my dear, in seas of fire. Unless you apply some balm to the anguish of this hour and say something nice to that young man there, life will run upon the rocks—indeed I hear the grating and the growling at this minute. My nerves are taut as fiddle strings. Another touch and they will snap” (Woolf 64).

Mrs. Ramsey is the force that unites the family and all those who stay at the Ramsey house. She puts her all into managing and keeping everything as she wishes it to be for the betterment of her family and friends. “Within this framework, Mr. Ramsay’s income provides the table at dinner, but Mrs. Ramsay and other women provide the food that decks the table. Indeed, the tender beef she serves is presented as her own flesh, which she sacrifices to bring the diners into communion” (Brivic 8).

While Mr. Ramsey indulges himself in intellectual work, Mrs. Ramsey does not have such a privilege. This is why she is so envious of her husband, Lily Briscoe, and her children—they are able to put their careers and enjoyment of their lives first, meanwhile Mrs. Ramsey is trapped in the caretaker role. “Nor is sympathy, the art of human relations, enough for Mrs. Ramsay; she is somewhat envious of her husband’s greater hopefulness because “he had always his work to fall back on” (Woolf 91). The word “work” is not used to describe Mrs. Ramsay’s activities of mothering eight children and a husband, running a large household, looking after the comfort of her guests, match-making, and visiting the sick and the poor” (Smith 10). Mrs. Ramsey’s motherly role hinders her from making the change she wants to see in the world. This leads her to self-loathing and dark thoughts, trapped in a role that does not allow her to achieve her dreams.

Mr. Ramsey’s character embodies the toxic masculinity of the nineteenth century father. He is commanding and sometimes cruel to his family due to his extreme sense of insecurity. He struggles to be vulnerable with everyone except for his wife, and depends on the female figures in his life for consolation after her death.

Mr. Ramsey establishes dominance over his family in order to find a sense of control in his life. His insecurities make him seek places where he can find power, and the main way he does this is through sovereignty over his family. This has a negative impact on how his children see him. James downright hates him, but Cam has conflicted feelings. “But what remained intolerable, she thought, sitting upright, and watching Macalister’s boy tug the hook out of the gills of another fish, was that crass blindness and tyranny of his which had poisoned her childhood and raised bitter storms, so that even now she woke in the night trembling with rage and remembered some command of his; some insolence: “Do this,” and “Do that,” his dominance: his “Submit to me.” (Woolf 114).

Mr. Ramsay experiences extreme insecurity over his intellect, constantly questioning whether he will leave an intellectual legacy after his death. This unreachable aspiration leads him to extreme anxiety, with a goal that is completely out of his control. “He is a philosopher by profession only, a local philosopher perhaps employed at a university or on the book-lecture circuit. He cannot get to R, he cannot get to Socrates; he cannot, that is, get to immortality, that patriarchal dream” (Donaldson 4).

Because of this self-consciousness, Mr. Ramsay seeks authority in the only way he can: establishing “tyranny” over his family. However, his frustration is in the fact that Mrs. Ramsay has such jurisdiction over family matters. She has a closer relationship with the children, and seems to always take the opposing side when he imposes his control. “The father should not be outside the window, looking at the mother and son in the window; the husband and wife should be together, the son with them both, but not between them, and most of all, not between the mother’s knees” (Pedersen 3). Mr. Ramsey feels feminized by his role in the family, angered by Mrs. Ramsey’s usurping of control. This leads him to have even more insecurities—imperfections, both intellectually and paternally.

Mr. Ramsey seeks pity and consolation for his insecurities in the female figures of his life: the only people he is truly vulnerable with. They are pressured with the weight of Mr. Ramsay’s mental health, forced to find some way to aid him. His mental stability is putty in their hands. “Will you not tell me just for once that you love me? He was thinking that, for he was roused, what with Minta and his book, and it’s being the end of the day and their having quarrelled about going to the Lighthouse” (Woolf 81).

Mr. Ramsey heavily depends on the women in his life, feeling their “job” is to console and comfort him. “All this self-pitying dramatization of his plight puts him into a state of anxiety which can only be assuaged by feminine pity, that of Mrs. Ramsay in the first section of the book, and of Lily Briscoe and Mrs. Beckwith in the third”(Baldanza 3-4). He perceives being vulnerable as a “feminine trait”, and the only people he can discuss it with are those who are female. If he discussed it with Mr. Carmichael, Bankes, or Tansley, he feels it would be shedding his intellectual superiority and overall strength.

This constant desire for sympathy weighs heavily on his family, especially in his daughter Cam. She feels conflicted, experiencing his ruthless nature towards his family as well as the kinder side of him. She wants to forgive him of his crueler qualities, but she remembers the draining impact he has had through emotional outbursts.

“The tone is very close to that of Mr. Ramsay in To The Lighthouse; it must have been stifling or oppressive for children in real life to be addressed with the full weight of this passionate man’s demands for sympathy, admiration, and forgiveness” (Hampshire 343). Woolf’s experiences with her own father bleed into her characterization of Mr Ramsey in To The Lighthouse, describing the tremendous weight he has on others because of his inferiority complex and self-pity.

Lily’s character represents the experience of the nineteenth century woman. She is not taken seriously for her artsmanship, only seen for her looks and not for her intellect. She is seen as inferior to her female adversaries because she is more focused on her passion than “settling down”, getting married, and having children. Because she does not abide by the standards of the time period, she is seen as inferior to her female adversaries.

Lily is not taken seriously for her artwork. Charles Tansley repeatedly tells her that women can’t paint—a thought that inevitably rattles her subconscious mind and makes her feel insecure of herself. She is only seen for her looks and her gender, expected to look pretty and provide sympathy to men; two concepts she is not well versed in. “She seemed to have shrivelled slightly, he thought. She looked a little skimpy, wispy; but not unattractive. He liked her” (Woolf 104). Mr. Ramsey judges Lily by how she abides by the gender roles of her generation. He sees her as lesser than because she does not know how to comfort and console. She is an artist, not a wife or mother.

Both Mr. Ramsey and Charles Tansley constantly undermine Lily, making her feel worthless due to her profession and nonconformity to the societal standard. This makes Lily frustrated. “She is, rightly, angry at Tansley’s oppressive male consciousness as it surfaces in his judgement that “women can’t paint, women can’t write,” for it annihilates her. Lily is angry at the contradiction: the man needs me, but does not want to recognize my self” (Gliserman 16). She is used only as an object of ridicule and solace, and is tossed aside when she is no longer useful.

Lily’s intensity for art is what keeps her from drowning in the currents of marital expectation. She is able to keep her own sense of self through focusing on her work, constantly thinking about where to move different elements and what strokes to use.“It is the resolution to move her tree to the center of the canvas that sustains her through the dinner party, protects her against Charles Tansley’s pronouncement that women cannot paint or write, and enables her to resist Mrs. Ramsay’s determination to marry her to William Bankes” (Cohn 4). Lily’s indomitable spirit allows her to avoid those who suppress her abilities, using her canvas and paintbrush in order to give her control of her life.

Lily, unlike other women of her age, has a passion. Her spark for painting sets her apart from the rest, but hinders her ability to be the sympathetic wife and mother expected of a woman in the nineteenth century. She is seen as inferior to Minta and Prue, as demonstrated by Mrs Ramsey’s inner dialogue. “Of the two, Lily at forty will be the better. There was in Lily a thread of something; a flare of something; something of her own which Mrs Ramsay liked very much indeed, but no man would, she feared”(Woolf 70). Lily’s love for Mrs. Ramsey makes her beliefs all the more prominent in her mind, and causes her the dilemma between artistry and becoming the maternal figure Mrs. Ramsey and society expect of her.

Lily is conflicted for the majority of To The Lighthouse, torn between her opposition to Mrs. Ramsey’s traditional ideals and love for Mrs Ramsey. At the end of the novel, Lily finally “accepts her singleness, her need to paint. She accepts and acknowledges her hostility to Mrs. Ramsay’s beliefs and machinations. Recognizing her love for Mrs. Ramsay, Lily moves beyond it to a love and respect for herself dependent on and integrated with her mature assessment of Mrs. Ramsay” (Lillenfield 2-3).

Lily’s epiphany with the completion of her painting is representative of the triumph of the nineteenth century woman. She breaks herself from the chains of societal expectation to cherish her individual self and finally let go of the overwhelming presence of Mrs. Ramsay’s constructs of marriage and bearing children.

“Lily Briscoe is the first of Woolf’s characters to escape the totalizing image of Woman, represented in the novel as Mrs. Ramsay, and the silencing presence of the Law-of-the-Father, appearing as Mr. Ramsay, and to find a way to represent a reality of women’s lives which is different from the figure of Woman” (Crater 2). Lily’s escape from societal expectation is symbolic of the female voices of the nineteenth century. They used surnames in order to publish their literature and art, paving the way for a new generation of women to be heard instead of silenced and creating the change they wish to see in the world.

While To The Lighthouse is a commentary on motherhood, toxic masculinity, and the female experience in the nineteenth century, Barbie is its twenty-first century counterpart. Gloria, Ken, and Barbie serve as parallels to Mrs. Ramsay, Mr. Ramsay, and Lily Briscoe. Mrs. Ramsay and Gloria are mothers ridiculed by family and society alike for their ideas and unseen for the immense work that they do. While Gloria is a career woman with a job at Mattel, she is just as trapped as Mrs. Ramsey, forced into unattainable societal expectations no woman can achieve. Mr. Ramsey and Ken struggle with insecurity, feeling unworthy mentally and physically. They are controlling of others in order to feel that they have power, and struggle to be vulnerable and admit their shortcomings. Lily and Barbie have to overcome the societal pressures put onto them, realizing that marriage is not their happily-ever-after. Lily learns to love her role as artist and painter, while Barbie learns that it is okay to just be herself. This set of parallels adds dimension to future readings of To The Lighthouse, allowing readers to further relate to the characters and compare and contrast the ideals of the nineteenth century to those of modern day.

Works Cited

Baldanza, Frank. “To the Lighthouse Again.” PMLA, vol. 70, no. 3, 1955, pp. 548–52. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/460057. Accessed 7 Nov. 2023.

BRIVIC, SHELDON. “Love as Destruction in Woolf’s ‘To the Lighthouse.’” Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature, vol. 27, no. 3, 1994, pp. 65–85. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24775769. Accessed 6 Nov. 2023.

Crater, Theresa L. “Lily Briscoe’s Vision: The Articulation of Silence.” Rocky Mountain Review of Language and Literature, vol. 50, no. 2, 1996, pp. 121–36. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1348227. Accessed 9 Nov. 2023.

Cohn, Ruby. “ART IN ‘TO THE LIGHTHOUSE.’” Modern Fiction Studies, vol. 8, no. 2, 1962, pp. 127–36. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26277247. Accessed 9 Nov. 2023.

Daugherty, Beth Rigel. “‘There She Sat’: The Power of the Feminist Imagination in To the Lighthouse.” Twentieth Century Literature, vol. 37, no. 3, 1991, pp. 289–308. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/441704. Accessed 3 Nov. 2023.

Donaldson, Sandra M. “Where Does Q Leave Mr. Ramsay?” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, vol. 11, no. 2, 1992, pp. 329–36. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/464304. Accessed 8 Nov. 2023.

Gliserman, Martin. “Virginia Woolf’s ‘To the Lighthouse’: Syntax and the Female Center.” American Imago, vol. 40, no. 1, 1983, pp. 51–101. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26303727. Accessed 9 Nov. 2023.

Hampshire, Stuart. “The Heavy Victorian Father.” Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism, edited by Dennis Poupard, vol. 23, Gale, 1987. Gale Literature Criticism, link.gale.com/apps/doc/GTIELR209629580/GLS?u=eahs&sid=bookmark-GLS&xid=dc5f3848. Accessed 7 Nov. 2023. Originally published in The Times Literary Supplement, no. 3959, 10 Feb. 1978, p. 159.

Lilienfeld, Jane. “‘The Deceptiveness of Beauty’: Mother Love and Mother Hate in To the Lighthouse.” Twentieth Century Literature, vol. 23, no. 3, 1977, pp. 345–76. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/441262. Accessed 6 Nov. 2023.

Pedersen, Glenn. “Vision in to the Lighthouse.” PMLA, vol. 73, no. 5, 1958, pp. 585–600. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/460303. Accessed 8 Nov. 2023.

Silver, Brenda R. “Mothers, Daughters, Mrs. Ramsay: Reflections.” Women’s Studies Quarterly, vol. 37, no. 3/4, 2009, pp. 259–74. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27740593. Accessed 3 Nov. 2023.

Smith, Susan Bennett. “Reinventing Grief Work: Virginia Woolf’s Feminist Representations of Mourning in Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse.” Twentieth Century Literature, vol. 41, no. 4, 1995, pp. 310–27. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/441533. Accessed 6 Nov. 2023.