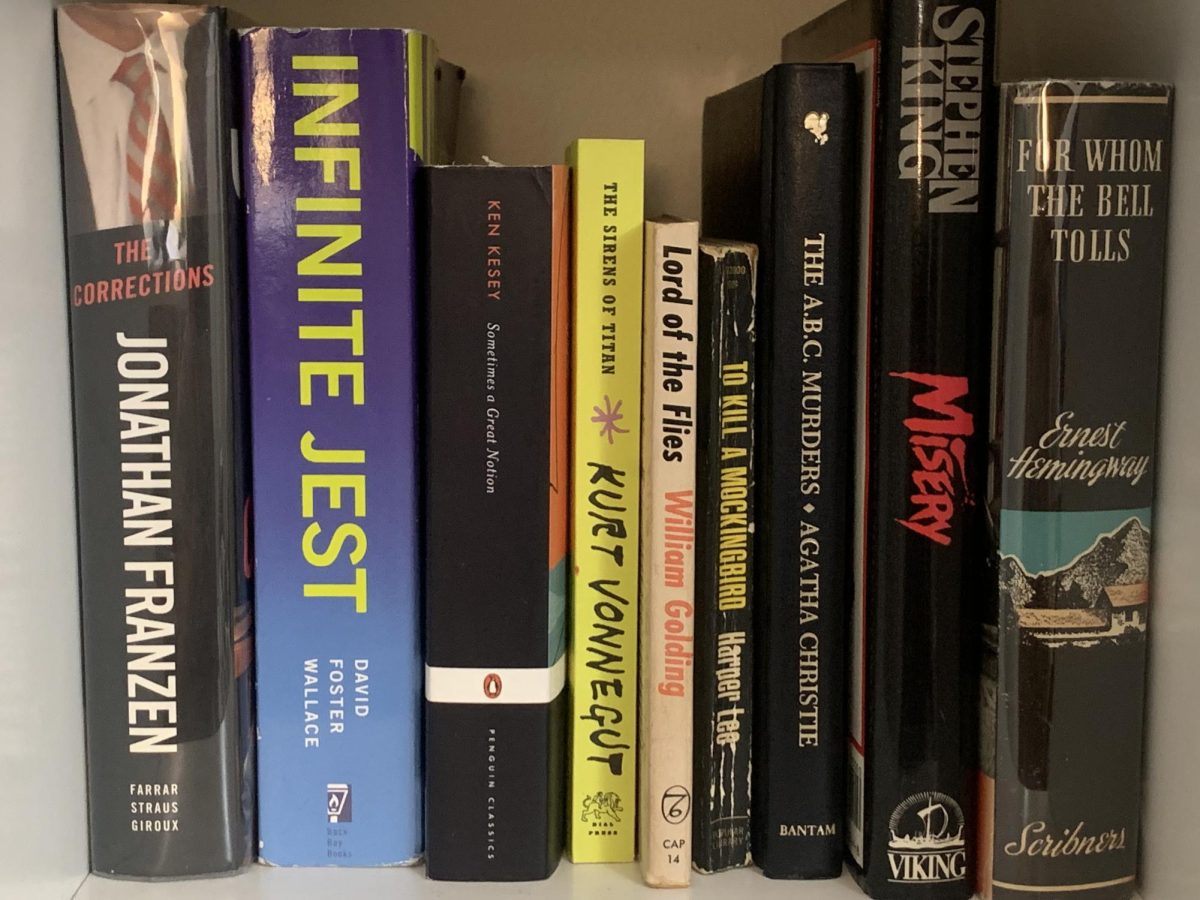

One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey is an integral piece of contemporary fiction. It follows Chief Bromden, a schizophrenic Native American, who is confined to the walls of Oregon State Hospital. He loses himself amidst the fog and monotony of his confinement until Randle McMurphy is admitted into the institution.

McMurphy is the novel’s hero, rebelling against the authority of Nurse Ratched and the female staff. To the patients, he is a savior, providing them cigarettes, alcohol, gambling, and prostitutes—a life of excess and enjoyment. Ratched prohibits this, as the men are patients in a psychiatric institution dedicated to their healing and growth until they can return as improved citizens into society. This, in turn, creates the vision of Nurse Ratched as the tyrannical, overbearing villain of the novel, through the lens of Bromden and McMurphy.

In Ken Kesey’s satirical novel, One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, he uses the unreliable male-centric perspective of Chief Bromden to highlight the objectification and toxic masculinity in the characters’ views of Nurse Ratched and the women around them. Their judgment and biases create a skewed perspective of Nurse Ratched’s character and intentions toward the inpatients.

The unreliable narration of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest impacts the reader’s view of Miss Ratched through the perspective of Chief Bromden. Bromden deceives the patients and staff by convincing them he is dumb and deaf when in reality, he has “been hearing all these years, listening to secrets meant only for their ears?”(Kesey 149-150). He is a skilled manipulator and eye on the inside, making him capable of convincing McMurphy and the others of his view of Nurse Ratched.

In Bromden’s reality, Ratched is an authoritative emasculator, stripping the men of their virility. She is a part of “the nationwide Combine that’s really the big force, and the nurse is just a high-ranking official for them”(Kesey 192). The Nurse is part of a nationwide system trying to take away their manhood and “feminize” them. “Big Nurse as satiric target becomes both victimizer and victim for narrative reasons”(Géfin 2), subjecting the men in the ward to admitting their weakness. “In all ‘true males’eyes, she becomes a “ball-cutter” because she frustrates male desire(Gefin 4)”.

Bromden, McMurphy, and their fellow men view Ratched as a sort of castrator. She forces them to discuss their vulnerabilities in front of their peers—one of which is Harding’s inability to satisfy his wife sexually. “‘His wife’s ample bosom at times gives him a feeling of inferiority’”(Kesey 44). The Nurse does not flaunt her own body in her uniform; an indicator of her professionalism and dedication to creating a safe space for her patients. However, her asexuality causes the patients to rebel in the only way they know how—sexualizing her.

Bromden takes part in this, imagining Ratched’s nightly routine. “At home she locks herself in the bathroom out of sight, strips down, and rubs that crucifix all over that stain running from the corner of her mouth in a thin line across her shoulders and breasts”(Kesey 165-166).

To a degree, Bromden understands Ratched’s dilemma. She is forced to abide by the ethics of the psychiatric system of the time. She may not agree with practices such as shock therapy or lobotomies, but she is required to take certain measures because it is her job. No matter how guilty she feels, Ratched’s career and the mistakes she has made are like a permanent stain that she can never be rid of. However, by objectification at Ratched’s expense, the men are temporarily able to regain their power. This revelation causes Bromden to share his ideas with the men in the ward, convinced that using Ratched’s sexuality against her is the only way to take her down.

The objectification and sexualization of Nurse Ratched are seen from the very beginning of the novel, where McMurphy starts to conspire with the men about ways to take the Nurse down. “‘And in spite of all her attempts to conceal them, in that sexless getup, you can still make out the evidence of some rather extraordinary breasts’”(Kesey 71). Harding feels inferior for needing help with his sexual issues, which causes him to project his insecurities onto Nurse Ratched.

By treating her asexuality as an illness that McMurphy must cure, he avoids the truth that he needs the help that Ratched provides. The men feel that McMurphy is their only hope—a man in his late thirties charged with rape against a fifteen-year-old. Nurse Ratched’s administration of the ward is a serious dilemma, and the only solution is to “‘ just throw her down and solve your worries, wouldn’t it?’”(Kesey 192). Their mental illness and objectifying tendencies make them see sexual assault as their “ultimate weapon”, rather than the crime it truly is.

The juvenile minds of the men cannot comprehend the moral complexities it takes to serve the ward as Ratched does, or the morally wrong nature of sexual abuse. As a result, they resort to objectification as a way to comfort and empower themselves. “The atavistic male myths of bonding, initiation, freedom, and sacrifice are ultimately accompanied by a representation of and an attitude toward women that is atavistic and brutal (and perhaps adolescent as well)”(Vitkus 120). The male perspective of Chief Bromden cultivates an increased sense of misogyny within the text. The reader receives a primitive view of Nurse Ratched—and this viewpoint is not limited to her character.

When Candy and Sandy—two sex workers—are introduced as chaperones to the fishing trip, the men gawk, encapsulated by the women’s physical beauty. “She was younger and prettier than any of us’d figured out” “all any of us could think of was that she was a girl, a female who wasn’t dressed white from head to foot like she’d been dipped in frost, and how she made her money didn’t make any difference”(Kesey 230). The patients view Candy and Sandy as forbidden fruit—a delectable prize only to be praised and devoured. They serve as antithesis to the “rotten” nurses, youth, and promiscuity within reach of the men in the ward. They crave what they cannot have, trapped within the walls of Oregon State Hospital. Their inability to escape leads them to toxic masculinity and increasingly rudimentary gestures, leading up to the sexual assault of Nurse Ratched.

The men of the ward feel hamstrung, their weaknesses put on display by a woman who, in their perspective, only wants to debilitate. “‘We are victims of a matriarchy here, my friend, and the doctor is just as helpless against it as we are’”(Kesey 63). The hospital is run by women asserting their dominance over men, and they are not equipped with the emotional maturity to speak about their feelings and willingly engage in pregnable discussion. They instead resort to physical violence and disrespect—a desperate attempt to give themselves some sort of control.

This toxic masculinity is seen when McMurphy tries to pitch his idea of watching the World Series to Ratched to no avail. Ratched sees the men try to watch the game instead of doing their mandated cleaning and turns the television off in an attempt to seize sovereignty. This has no impact on the men, as they rebel “lined up in front of that blanked-out tv set, watching the gray screen just like we could see the baseball game clear as day”(Kesey 144). This blind disobedience demonstrates to Ratched as well as the reader the mindset of the men in the ward. They feel that their rule is above hers, and disregard her ideas—even if they are beneficial to their societal return.

To the patients, Ratched is a villain, trying to castrate and cut them down. She removes their ability to do things that are stereotypically masculine, such as watching a sports game, going fishing, or smoking a pack of cigarettes. The deluded men see her actions as an attack and convince McMurphy to fight back in the only way they feel is fruitful—rape. The novel’s climax is the sexual assault of Ratched; a crime seen as a courageous feat by the patients of the ward.

Only at the last—after he’d smashed through that glass door, her face swinging around, with terror forever ruining any other look she might ever try to use again, screaming when he grabbed for her and ripped her uniform all the way down the front, screaming again when the two nippled circles started from her chest and swelled out and out, bigger than anybody had ever even imagined, warm and pink in the light—only at the last, after the officials realized that the three black boys weren’t going to do anything but stand and watch and they would have to beat him off without their help, doctors and supervisors and nurses prying those heavy red fingers out of the white flesh of her throat as if they were her neck bones, jerking him backward off of her with a loud heave of breath, only then did he show any sign that he might be anything other than a sane, willful, dogged man performing a hard duty that finally just had to be done, like it or not. (Kesey 319)

The scene, in essence, is a final battle against Nurse Ratched and the matriarchy of the hospital. McMurphy reacts with violence after Ratched tells him that Billy’s death was due to his faulty morals and guidance. He uses raw strength and sexual power to expose Ratched’s breasts, and attempt to assert his toxic masculinity before he is lobotomized. McMurphy, Harding, Bromden, and the others feel that “it is only the sexual violation of the Big Nurse that can guarantee a conclusive victory for the men of the ward. Only this can get to the root of the trouble and restore their lost masculinity”(Vitkus 19). McMurphy is described as a sane man, knowing he was morally wrong in his act. However, the misogynistic culture of the ward portrays sexual assault as a way to overrule; restore their masculinity while revoking the rights of Ratched. It “had to be done”, even though they could have gotten through to her by shedding their masculinity for a moment. Her traumatic experience is triumph to them—a final defeat of the damsels attempting their defenestration.

One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest uses its male perspective to highlight the toxic masculinity of the patients and the time itself. McMurphy, Bromden, Harding, and the men of the ward, feeling powerless, shift the system, making Nurse Ratched the victim of sexualization, objectification, and rape through their male-centric gaze. The novel, while published in 1962, remains relevant today. Toxic masculinity is ever present, with around 463, 634 individuals a year becoming victims of sexual assault or rape(National Crime Victimization Survey 2019). Rape culture is on the rise, and Nurse Ratched’s sexual assault at the end of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest leaves audiences pondering one thing: “Has rape culture truly shifted in the last 62 years?”