A Reach for Justice in Mockingbird

To Kill a Mockingbird Review Schubert Theater, NY Broadway

A potato sack is a common item. It’s either a staple to Southern agriculture or a toy in the North for potato sack relays in school.

But for the citizens in Maycomb County, Alabama, the potato sack can be a sign of entailment, the exchange of goods rather than currency to financial pains. A potato sack can also take on a more sinister intention, when worn over your head as a Ku Klux Klan member, with lighted torches, heading for a lynching.

Potato sacks resonate a new form of identity for a new interpretation of the modern age in Aaron Sorkin’s adaptation of Harper Lee’s classic novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, starring Jeff Daniels as Atticus Finch, famous for his ever varied parts in the HBO series, The Newsroom, and the movie, Dumb and Dumber.

After reading the book twice, once in elementary school and once in 9th grade and watching the movie the summer before sixth grade, I approached this play as a new interpretation of the novel.

And that is as it should be.

The play took on its own form, paying tribute to Lee’s vision, but also modernized with Sorkin’s quick paced dialogue and scene changes. Scattered musicians on organ and guitar played on the fringes of the stage, right when the play began, marking transitions.

The play transitioned seamlessly from the courtroom to the Finch household. With these settings in mind, a play is limited to its exposure, considering a flashback or quick scene cannot easily be captured in one blackout. However, the front porch, tree branches, and witness stand seamlessly flowed as if they delivered lines.

Speaking of seams, the production costumed a more subdued, casual attire, appropriate to the class levels and time period.

The play placed the three young children, Scout, Jem, and Charles Baker Harris Jr. “Dill,” as the narrators, impeccably played by adults. But not in an annoying way. Rather, the actors were an endearing, enlightening reflection of one’s past, recognizing skeletons never realized in the photo albums.

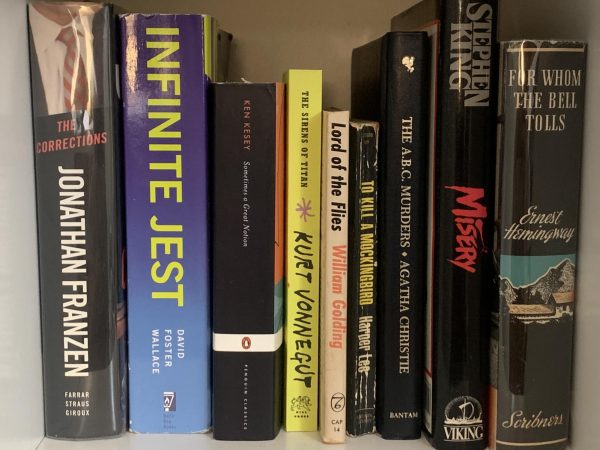

The play intended to label the five social classes of Maycomb County: the educated, the townspeople, the farmers, the poor whites, and the African Americans. Not all of these ‘ranks’, however, were represented in the production. Much of the play centered around the discrimination of the African Americans, in the court case against an negro field worker, Tom Robinson, played by Broadway debut Gbenga Akinnagbe, accused of raping a white farmer’s daughter, Mayella Ewell.

Sorkin added some great comedic bits, sometimes a tad dark, when it came to the young children growing up in the town. For instance, the events in which Jem lost his pants while sneaking around Boo Radley’s house became funnier when Dill said they were playing strip poker to Atticus. As mentioned earlier, these parts only vamped the true beauty of Lee’s novel.

It is hard to reach justice when you cannot see a place for yourself. The play could have better achieved this: their sense of empathy with the characters building together. We see them in their select environments (more or less), but never in a collected, empathetic space. Not even a courtroom would depict this.

Regardless of setting, the play upheld a great sense of pacing. No part ever sagged under the pressure of the play’s heavy message. This message, pertaining to the empathy required amongst all levels of society, is especially present in the modern age. There are mockingbirds, victims, in the present day, whether they are on the streets or at the border. All it takes is to walk in their shoes, to see their perception.

Jeff Daniels also captivated a performance worth noting, as his on stage chemistry with his children and with their maid, Calpernia, felt as if they could truly be a family, inside the safe space of their abode.

Even in today’s current events, class systems still exists. Prejudice exists. Racism exists. Classism exists. When Tom Robinson claimed he felt sorry for Bob Ewell’s daughter, he socially stepped out of the pyramid, rolling out of the potato sack.

Why? Because he was below her?

After all, he saw her as a fellow human in an abusive predicament. There is no color to hardship. To walk in the skin of another man, as Atticus Finch would say, is an important aspect of being a human being. We never know the full truth of a person’s testament, just as there are many ways to use potatoes.

There is a fine line between justice and security.