Rachel Corbett explores the brilliance behind artists Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin

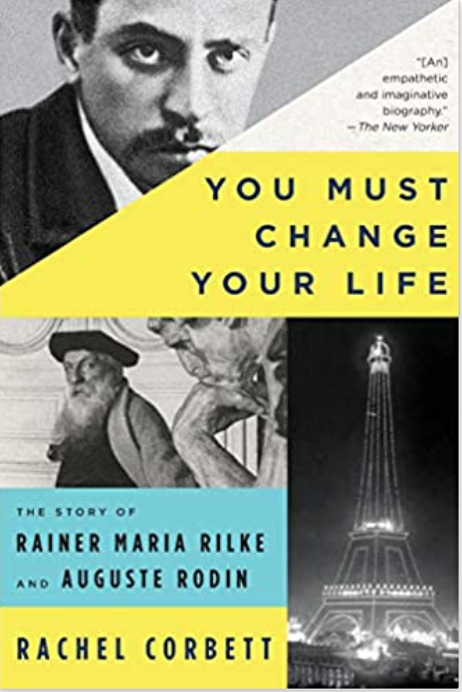

Influences in Life and Art, a Review of: You Must Change Your Life: The Story of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin by Rachel Corbett You Must Change Your Life: The Story of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin by Rachel Corbett. 301 Pages. $11.99

“Travailler, toujours travailler,” or in English as I understand it, “Work, always work,” is a phrase used a total of five times throughout this biography each to be interpreted in different ways as the author, Rachel Corbett guides her readers through a tale of the intertwined lives of two men.

“Travailler, Toujours travailler,” or in English as I understand it, “Work, always work,” is a phrase used a total of five times throughout this biography each to be interpreted in different ways as the author, Rachel Corbett guides her readers through a tale of the intertwined lives of two men. These two, as indicated by the title of the book, are Rainer (René) Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin, a poet and sculptor respectively. They came from different ages, different countries, different languages, yet somehow their lives became unmistakably tangled.

The phrase was first coined by Rodin in the book. “He understood that Rilke was a fellow artist, and so he framed his stories as lessons that the young poet might take as examples. Above all else, he stressed to Rilke, Travailler, toujours travailler. You must work, always work, he said. ‘To this, I devoted my youth.’” (Corbett, 84) But the man himself had followed that doctrine of his for years.

From his youth to his middle age, as described in “Part One: Poet and Sculptor,” seemed destined to become obsessed with art. He had been uninterested in traditional education, instead of more interested in a physical labor type job where he could use it his hands. He started withdrawing, learning from his teacher Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran, putting pencil to paper to draw what he saw as an outline, and then filling in the details. “He [Lecoq] believed young artists ought to master the fundamentals of form only so that they might one day break them. ‘Art is essentially individual,’ he said.

The purpose of the memorization exercises was actually to allow the artists time to acknowledge their reactions to a picture as its properties unfolded to them. Did a gently arched line produce feelings of serenity? Did a densely wound shadow evoke anxiety? Did certain colors trigger memories? …” (Corbett, 13) This sort of style would stick with Rodin to his ancient years as he based his sculptures based on his impressions of the subject rather than simply copying the subject.

From drawing, he moved on to what he would be most popularly known for, sculpting. He would devote hours and hours to work for money to pay for models so that he might sculpt them, and then spend more hours sculpting them to perfection. He wasted very little time on the frivolous matter of life or of relationships, allowing the woman who would eventually stand by him all his life, Rose Beuret, to be neglected, along with their child. He lived by the phrase “travailler, toujours travailler” and never let anyone believe otherwise.

When Rilke would walk into his life through an introduction of similar friends (Rilke’s wife, Clara Westhoff), he would be awed by Rodin’s work, his environment, methods, and accomplishments. After he would attempt to adopt that same phrase into his life in much the same way he saw Rodin doing, condemning everything in his life that he thought might slow him down. “Rodin’s mantra, Travailler, toujours travailler, contradicted everything Rilke had learned about the fusion of art and life in Worpswede. But the poet had spent years watching the clouds, anxiously awaiting a muse that never came. Rodin’s example gave him permission to act. Now, to work was to live without waiting.

More than that, Rilke concluded, ‘to work is to live without dying.’” (Corbett, 92) For Rilke, in Part Two, would be the disciple, and Rodin would be the master. Rilke, through connections made through Rodin and his friendship with him and its benefits, would idolize the man for as long as he could.

“Travailler, toujours travailler,” Rilke would leave behind his family, his wife and daughter that he thought would make him an adult, would leave his home almost permanently to live a great amount of time in Paris, and would attempt to dedicate himself so fully to his work that he’d never actually live despite his rationale to work was to live without dying. He might not be dead but he never seemed to be fully living either. “Becker wrote to her husband the next day. ‘Ever since Rodin said to them, ‘Travailler, toujours travailler,’ they have been taking it literally; they never want to go to the country on Sundays and seem to be getting no more fun out of their lives at all.’” (Corbett, 105) It was always justified by whatever work he spit out because of it. “He had heard his master’s words—travailler, toujours travailler—and it had resulted in probably the most productive period of his career to date.” (Corbett, 195)

These works of Rilke’s were different, however. Most notable from his workaholic days would have to have been his New Poems, which, as implied but their title, was completely different from any other work he had written before. It examined the subjects observationally from all angles. It was unsentimental and was compared to Cubism, a movement that had been growing in the art world at the time the poems were written. Rilke referred to them as

“thing-poems.” If it had to be summed up, it would almost seem like it was Rodin’s work in written form.

Originally, he had written of his own experiences and feelings at the time of their happening. But in his need to produce, to emulate his master, it seemed that he had lost something of himself along the way. This was later compounded by the day that he would find that the doctrine that Rodin, his idol lived his life by, was not one Rodin followed to the letter.

“When Rilke had heard the directive travailler, toujours travailler, he followed it literally, abandoning life in anticipation of a future payoff. When he saw that Rodin had not followed this mandate himself, he felt betrayed. But his mistake was failing to grasp that Rodin could never tell Rilke how to live. The best any master could do was encourage their pupil and hope they find satisfaction in the work itself. In art, Rilke had started to realize, there was never anything waiting on the other side: There was no god, no secret revealed, and in most cases no reward. There was only the doing.” (Corbett, 239)

This book is a biography of the two people whose names are on the cover, but it is also a biography of those lives they touched and how they influenced and were influenced by them.

Was the main focus on the influence that Rodin had on Rilke? Yes, but it goes far deeper than simply that. It was not on Rodin’s death that Rilke mourned in the book, for he mourned the death of his friend as well. One could not claim Rilke’s only friend to be Rodin as he held Lou Andreas-Salomé in the highest of opinion to his death bed. It is why he could try to move on past this betrayal.

“Rilke had decided, ‘Perhaps I shall now learn to become a little human.’” (Corbett, 239)

This book was beautifully written. The words, descriptions, hooks, and appealing characterizations made it a hard book to put down, but also one of depth that takes time to read. The details of both men’s lives were laid out in an understandable and connected way that made the book easy to follow while also being a heavy read as it delved into topics of sex, sexuality, culture, war, belonging, and identity. Above all else, however, it focused on life and art and the things that can influence it. It is a book that I think most have the capacity to enjoy, as it spans multiple topics that can strike a chord with every one particular of individuality and identity. It

is a book about two menu experiences on being human and how to make the most of life, which is something I think everyone can relate to on some level.

“Travailler, toujours travailler,” work, always work, were the words that started a journey of living for two men, and an identity crisis for the younger of them. If nothing else it is something to relate to, to understand, and to learn from, a valuable lesson that would be brilliantly taught by Rachel Corbett in her story of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin.