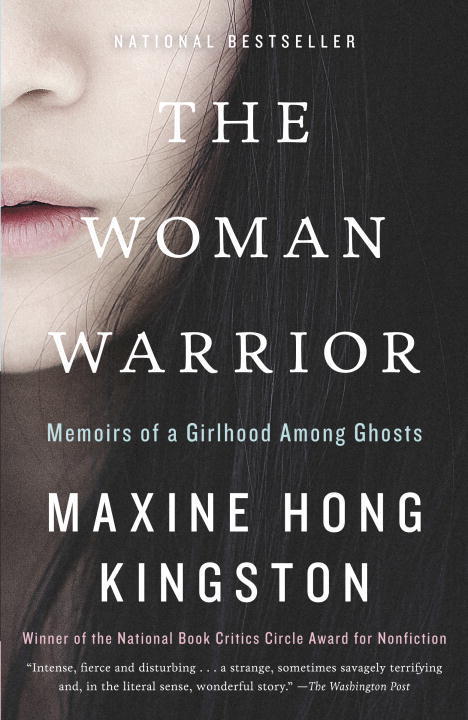

The Woman Warrior: Chapters of Strength and Oppression

A review of Maxine Hong Kingston’s memoir

A gripping memoir that tells of a young Chinese girl experiencing both the struggles of her old and new culture alike.

A broken nation littered with political and cultural unrest. A collective group of people, painfully torn apart by the red scythe of the Cultural Revolution. A girl, struggling with her own cultural identity, when her parents escaped the clutches of the scythe-bearers.

Maxine Hong Kingston, a Chinese American woman, was born on U.S soil after her father had escaped China’s Cultural Revolution in 1940. Mixing the beautiful yet painful memories of her autobiography, and the tales of a powerful folklore, she paints a picture of a woman’s societal roles both in traditional Chinese culture, and the westernized version of it.

Consisting of five interconnected chapters, “No Name Woman”, “White Tigers”, “Shaman”, “At The Western Palace”, and “A Song For a Barbarian Reed Pipe” all recount the cultural experiences of her family, and the tales of inspirational folklore. Each of these chapters can be read as short stories, where Hong Kingston reveals how folklore and the maternal members of her family influenced her to be the woman that she is today.

“No Name Woman”: a title that was appropriately given to Hong Kingston’s aunt who was shunned by her family members. The family tale begins with a secret that’s been sealed within her father’s side of the family, even going so far as to completely wipe her aunt’s existence from their memories.

“You must not tell anyone what I am about to tell you. In China your father had a sister who killed herself. We say that your father has all brothers because it is as if she had never been born.” (Kingston 8).

It’s in this very first sentence that we sense the notion of extreme pride within a Chinese family, especially in the fidelity of a woman to her husband. But in her aunt’s tale of misfortune, the only sister among a band of brothers became pregnant years after her husband had sailed for America in search of gold. “No one said anything. We did not discuss it. In the early summer she was ready to have the child, long after the time when it could have been possible.” (Kingston 8). The mother’s words here essentially imply that the pregnancy had happened due to infidelity, which is a logical choice considering the timing of the pregnancy.

“Talk-story” is the language of Hong-Kingston, and talk-story is precisely the tool that recounts the hypocritical expectations placed upon Chinese women. Her mother’s disdainful depiction of her aunt is talk-story. Similarly, Hong-Kingston learns of the impossible beauty standards of Chinese women through her mother’s talk -story. “Women looked like great sea snails-the corded wood, babies, and laundry they carried were the whorls on their backs. The Chinese did not admire a bent back; goddesses and warriors stood straight.” (Hong Kingston 12). Responsibilities of a mother require a disfigured body, but the Chinese community scoffs upon the lack of beauty. In the early 1900s, a Chinese woman was a paradox, both within her own body and her society.

Chinese women are beautiful creatures. Not hindered by their sexual desires and certainly not by the stereotypical frail female body, female warriors are able to achieve true victories of war, much of which far surpasses the victories of a man. At least, that’s what the legends told, especially of the Chinese heroine, Fa Mulan.

Every Chinese or Chinese-American knows the tale of Fa Mulan, whether it’s from the animated Disney film, or from the childhood stories that were uttered from our parents’ lips. Warrior, inspiration, determination, and strength; indeed, Hong Kingston was just one of the thousands of girls who grew up hearing about this woman warrior.

However, “White Tiger” is quite different from the westernized version of the story. For one, there’s no mythical red dragon to give Mulan advice. Rather, there is a magical water gourd that allows Mulan to see the far expanses of the earth on its rippling surface. Syncing one’s senses to the forces of the earth, following the virtues of monks, and the calm revenge of a daughter all play a factor in Fa Mulan’s unwavering strength in battle. “Copying the tigers, their stalking skill and their anger, had been a wild, bloodthirsty joy. Tigers are easy to find, but I needed adult wisdom to touch dragons.” (Kingston 24).

But magic and mythical creatures hardly play the overarching large role in this tale. It’s instead the defiance of the stereotypical weakness of a woman back then in Chinese culture.

Hong Kingston writes “She said I would grow up a wife and a slave, but she taught me the song of the warrior woman, Fa Mulan. I would have to grow up a warrior woman.” (Hong Kingston 18). In a way, this folktale was incorporated to utter both a cry of despair and hope. A cry of despair for the armor she will have to build up for her dull future, and a cry of hope that longs for a more fulfilling life.

“Shaman” offers a look into the modern expectations of a Chinese woman, this time exploring the spiritual and scholarly successes of Hong Kingston’s mother. “The Keung School of Midwifery awards its Diploma to my mother, who has shown through oral and written examination her Proficiency in Midwifery, Pediatrics, Gynecology, ‘Medecine,’ ‘Surgary.’ (Kingston 42). The list of her proficient fields go on, even including the profession of “bandage”, which may be Hong Kingston dabbling in some sarcastic satire.

Without a Chinese woman’s oppression-filled duties at home, the westernized version of these suffocating expectations are instead placed in academic potential. Fidelity within a family may no longer be relevant anymore, but the gap must be replaced with a scientific or medical degree sufficient enough to sustain a Chinese family’s pride.

Jumping ahead into the 21st century, this notion of complete academic success is still prevalent in many Chinese-American families. A cruelly accurate parallel between the mother’s century and our own, in fact. In my own Chinese household, Ivy Leagues are the standard. A degree in the arts is forbidden. But most importantly, “Do well. Make your family proud.” Look on the bright side though, at least I’m not to be shackled as a slave to a man.

“At The Western Palace” and “A Song For a Barbarian Reed Pipe” serve as sister chapters, depicting sacrifices of love and cultural language. “At The Western Palace” reveals Hong Kingston’s mother’s name as Brave Orchid, in which her sister Moon Orchid had recently moved to the U.S from Hong Kong. As we’ve learned in the first chapter, all of the men in both parents’ families had rushed to the U.S in search of gold and prosperity. Moon Orchid’s husband was no exception, and the chapter picks up years later just as the lovesick wife eagerly saved up enough money to join her husband.

Unfortunately, her husband had started a new family during his time in the U.S unbeknownst to his first wife. Once Moon Orchid became aware of her husband’s infidelity, she plunged down a psychologically dark road of delusions and hallucinations, where she eventually perished while the sun showered prosperity on her former husband.

“A Song For a Barbarian Reed Pipe” displays a similar type of sacrifice, but this time concerning Hong Kingston and her mother. Chinese culture is very important to the average Chinese woman, where I could even say that it is in their lifeblood to pass on the traditions to their children. This is certainly true for Brave Orchid, who painfully begins to recognize the need for her daughter to learn english in order to succeed in the U.S.

“But how can I have that memory when I couldn’t talk? My mother says that we, like the ghosts, have no memories.’ (Kingston 113).

With no way of communicating with her American peers, Hong Kingston did indeed continue to live as a ghost in the public, unable to share her talk-stories with her foreign world. It was at this time where Brave Orchid knew she had to sacrifice her cultural reservations, and push Hong Kingston to learn english.

The Woman Warrior is a truly raw depiction of a unique Chinese immigration story, revealing both the dark standards of a Chinese family, and the inspiring Chinese folktales that gave strength to Hong Kingston. Written as a memoir to her inner child, Hong Kingston delivers an unspoken tale of the outcast aunt, the ferocious warrior of Fa Mulan, the pitiful Moon Orchid, and a reflection of herself growing up in the wild U.S.