What’s up with “finna,” “fam,” and African-American Vernacular English words?

Is there a problem with AAVE in society today?

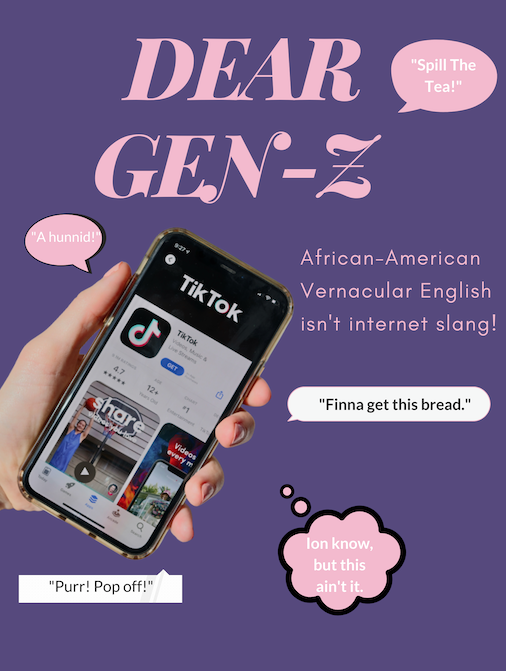

Gen Z should know that AAVE words are not solely recognized as “internet slang.”

In 2021, any teenager might stroll into the crowded halls of their middle or high school, join their group of friends perched against the metal lockers and greet them with, “What’s good, fam?” They’ll trade laughs and talk in loud voices, with sentences like “I’m finna go off this weekend” and “Stop capping” flying around. A teacher might walk by and mutter under his or her breath, “these kids and their slang.”

Words and phrases like “on fleek,” “periodt,” and “snatched,” to name a few, are in the daily vernacular of Gen-Z. They smile at their phones, thumbs twiddling away, texting words such as “purr” and “bae” because they’re trending in the TikTok comment sections. However, some Gen-Z members don’t know that these words are buried into history and already have a name, entitled African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) or Ebonics.

AAVE has a controversial origin. Some critics suggest that it originated after African slaves arrived in America, in their attempts to learn their captors’ language. Other critics suggest that AAVE was already a language: a mix of Creole and various West African languages. In 1996, it became known in the Black community as Ebonics, which is a portmanteau of the words ebony (black) and phonics (sounds).

At the time, the Oakland Unified School District tried to use AAVE as a way to help Black children understand standard American English, and attempted to declare it as its own language. This only caused a spark of outrage, as people questioned things like “ain’t ‘ain’t’ a word?”

How is AAVE grammatically written? There are many rules of AAVE; to name a few, compared to standard American English, AAVE excludes to-be verbs like “is” and “are.” For example, “he be workin’” or “I know you playin.” AAVE also uses negative concords (double negatives), which is a huge grammar red flag in standard American English. If an English teacher heard you say, “Can’t nobody say he ain’t workin,” they’d correct you, but this is acceptable in AAVE.

What’s the problem with AAVE in society?

The short answer is racism and linguistic stigma. Many of the things Black people do are defective in America, so it’s no surprise that the way they speak is one of them. To grammar police and other linguists of the world, AAVE is “broken English” or “lazy speaking,” and those who use it are considered uneducated and unsophisticated.

AAVE reaches a massively-wide audience when rappers such as Drake, Jay-Z, and Kendrick Lamar use it. Hip-hop and rap artists commonly use AAVE, sometimes even creating new words.

Because of this exposure of culture, it’s okay to rap in AAVE, but not speak it in a professional setting or around people who don’t speak it. This opens up a new can of worms, inviting breathy slurs like “ghetto talk.” Because of this, some Black people will code-switch (when Black people switch the way they’re speaking and acting to interact with those around them, usually colleagues).

Personally, I’ve been told that I speak “eloquently” or “White” when I’m not using AAVE. I’ve also heard people say things like “I’m using a Blaccent” when they’re not Black themselves, as if to mock the way some Black people speak.

At the end of the day, members of Gen-Z should understand that phrases like “chile anyway,” “sis,” and “real one” aren’t internet slang, nor are they solely part of vernacular. They have a history that we are partaking in. So, please be aware that it’s nothing new, before “the OG’s put you on blast.”

Roberta Poirier • Apr 24, 2023 at 3:37 PM

I wonder why we expect the Chinese, Vietnamese, Japanese, Italians and anyone other than people born in America to speak English? Proper English. I’m curious as to an answer. I’m half Asian, my mother spoke no English when she arrived in the US. And yet, she learned to speak English. Proper English. Not slang. I’m personally find it confusing. Please don’t tell me I need to widen my knowledge of languages. If I moved to another non English speaking country, I had better learn to communicate in that countries language.